Time Cyborg/Cinema Ruin

The first DVD I asked my parents to prioritize above their own in our Netflix mail queue was Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. I had seen an image of a poster for it somewhere in the blogosphere of about 2004. For something I had never heard of— a silent German interwar film— it felt uniquely familiar. With the benefit of now two decades of hindsight, I cherish the sense of innocence held in this memory. It’s just a genealogical fact to me now, that all of cinema and science fiction owes foundational debt to this film. Of course C3PO is a dream of Rotwang’s Maschinenmensch, of course the yawning chasm of the metropolis, crossed by tiny aeroplanes and stilted monorails feels like a relative of Blade Runner’s Los Angeles and Akira’s Neo Tokyo. Metropolis felt familiar because it pervaded and influenced so many things I had experienced as contemporary, even by the time I was 12.

It’s a film that continues to delight through an expanded universe of its own legend, as it’s visually called back to in so many films. It gives me a specific delight to decode a reference to it in another vision of the future— and there are a lot of futures made of or at least built atop 1927. On one level it feels good to be in on something fairly niche and detail oriented, of finding an easter egg, but there is also something else going on. It’s as if the zeitgeist of this silent film has had its surface tension relaxed by constant handling from the real mundane futures that have found it. It’s like 1925-27 and the time of the the homage begin to exist as something maybe more like Bakhtin’s Chronotope of literature, in which the ability to transcend the limitations of time becomes the form itself. Setting aside more detail oriented analyses of the materialism of the movie, Metropolis is “the future” and it can be reached from whenever you have the coordinates because it is safely archived in the past.

Cinema has a specific time form; a film is dreamed during pre-production, manifesting first as paper architecture responding to a script or treatment which at minimum summarizes the intent for the filming. All photography depends on the principle of excluding the entire world in favor of what is framed to convey narrative, so a plan, however abstract, is useful. But film narrative can also be built exclusively from the frame inwards. It could be months-years of design and fabrication to produce a series of set pieces and costumes before preparing the actors. In Metropolis’ case, the invention of a world is in the more literal sense. It had a production period of 17 months, during which plaster and wood hallucinated a future conceived on drawing boards in nearly the same place and time as those at the Bauhaus. The zeitgeist of the Wiemar Republic is part of the lasting resonance of the film. It took the hallucinogenic qualities inherent to the expressionist visual method and cooled them into the kind of rational fantasy that modern films and video games have normalized a century later. And while the Bauhaus, and the Republic only lasted a few years longer, the Metropolis still stands... somewhere…

But if it seems like ambitious production design and subject matter assured the films memory, I suggest watching with its original score— the gravity of 1927 is much harder to escape. If somehow the original poster I saw had a musical component, I might not have been so intrigued. I think one of the main reasons that the film isn’t a mass media attraction in the way some of its inheritors are, is simply because it is most available with its original score by Gottfried Huppertz, which limits the appeal to a few kinds of nerds basically. But the film has a surprisingly long list of scores created for it by musicians, artists and cultural institutions in dialogue with the original, and with the images themselves in every decade since release.

So today, the film is seen engaging with time in several ways that resemble the sense of architecture embodied in the ruin— the increment of time that is given proportion, harmony and meaning, given firmness in a final edit/print, then undergoes a saga of generative loss resulting in many new hybrids. In the sense of an architectural ruin pertaining to an old building, over the years, centuries and and millennia, it becomes an collection of palimpsests from its many users and owners and the changes they make to its original order, the care they prioritize or neglect, and the external forces that visit the site. The theoretical ‘completion’ of an architecture is when it is disassembled as if by time itself (a desert Tell mound as archetype). Time has consumed the ruin in the sense that we stand after it, looking at its architecture in a way not so divorced from how one looks at a plan drawing, where it is all simultaneously there outside of rational space, on the page. When faithful restorations are made they draw on both original stonework and timber as available and also on the paper folio-form of a building, in which the many chapters of changing ownership, renovation and calamity animate the surviving relics. Thus a pedigree is established with a nonexistent parts of the ruin through less-physical information forms, documenta, ephermera, forms as virtual as existed before an actual cyberspace.

In Donna Harraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1985) a confluence of developments in the 20th century provided the ground for a myth of dissolving boundaries, hybrids and dualism: the cyborg. Evolution merged the domains of animal and human, mechanical Industrialization fused animal-humans and machines and Microelectronic technology blurred together the physical and non-physical. Metropolis in its late form is ruinous in its accumulated meaning, being like a chronotope of a world that was still coalescing in the decades that followed its release, and likely a contemporary point of reference for ideas of progress towards a … real future (present) in which popular homages to it are yet divorced from the origin. Something cybernetic, the film has become a dualistic hybrid of the past and future, a time cyborg: past-seeding-future and its eventual result coming to know its prescient origins through later perversions. From the present, the film and all its referential resonance are like the many pages of a set of building plans for a future that was only partly built, or the compacted strata of a ruined tell mound. From this angle, we are able to glimpse outside of time and across reality itself.

Peep show

Continuing my research on moving image formats, I’ve been very interested in the mutoscope. Flipbook machines were part of how silent cinema was popularized in its earliest era. A rotary flipbook was driven by hand crank and viewed through a magnifying eyepiece. Inside the metal case, 850 cards fan out from a round core, each printed with a sequential frame. When the crank is turned, it plays at about 14 frames/second, strobing a moving image for a minute. I’m struck by the similarity with the short form video that has become predominate on apps like tiktok and instagram.

Mutoscopes were also called folioscopes. Along with Edison’s kinetoscope, which used film loops in the same way, with a single eyepiece and coin operation, they were some of the first ways the moving image was presented. Before large scale projection had been engineered, the problem of monetizing the viewing of short animations was solved with these vending machine-like outlets. They’re like if a film storage cask had mutated into a mechanical theater. The rotary flipbook has a similar sense of being a mutation of film stock stored on a reel. As close as I could abstract it, its almost like an analog instance of a codec or interlacing pattern; linear (film) or planar (flipbook) frames.

The mutoscope machine bears a resemblance to the machinery of the camera in a similar way to how projectors do. Like projectors and televisions, it’s a scale format of the Cinema. I find it an interesting one because in its original use, which it was designed for, it existed in a kind of public space that became sick and died over the twentieth century, which is attested to in the changing fates of the humble hand-cranked theater. For the scale of the object itself, something about the public placement of the machine, and the scale-play of the tiny, magnified moving images that live inside, in a warm light. On the altar-like ornamented metal canister, the eyepiece is at a height accessible to both children and adults (they’d as often be loaded with cartoons as smut). The average man would bow by necessity to turn the crank after dropping his coin in.

In terms of soundtrack the mutoscopic films are silent, only emitting a muffled chatter that evokes the genuine mechanical commotion of a film projector, amidst the white noise of the usually busy place the machine was placed. The images similarly do not flicker in exactly the same way as in film projection, but could almost be said to flutter, as they advance and burst toward the viewer at the speed of the motion. The effect is more or less the same though, because for the flutter to occur and the images to animate there is only one speed, forward. If one stops turning the hand crank, the flipbook goes slack, and flaps back against the card where the image had appeared. Each image that flutters past when in motion is first held in place for a fraction of a second, by a detente, and it is against this point that the rest of the spool will return if not pulled forward by the crank. The only point of tension with the structural points that define cinema is that the moving images are lit externally by light and aren’t as stencils giving it shape in shadow. But mutoscopes elevated the flipbook to a near-indistinguishable scale instance of cinema. Their obscurity today seems to me to be more about the course of their declining use, than anything necessarily about the their competency as an alternative cinema, in much the same way that comics related at one point to genre fiction in the main before a long relegation to outsider art and an eventual resurrection as competent media.

The flipbook conceit of the mutoscope is what allowed it to hold a patent in spite of Edison having one for the Kinetoscope, which achieved the same ends by cranking a loop of actual acetate film. It turned out that the flipbooks were much, much hardier than early film and before long the tempermental nature of the kinetoscope led to its decline. But for decade, after decade, after decade, the mutoscopes continued to collect change in amusement halls. So much so that their coin mechanisms needed to be updated several times to keep up with inflation. So much so that they outlived any public memory of the ‘amusement hall’, with a few practically outliving their descendant, the video arcade. Most met the end of their duty when the porno theaters of the 1970s closed in the late 1990s-mid 2000s, as the internet ushered in a new era of short-form smut, which bears some symmetry to their “what-the-butler-saw” peep-show origins, as prude as they may seem to us now. They can still be found at seaside attractions, where like much of the urban fabric, their seedy midlife is glossed over.

The scale factors all throughout this extinct media fascinate me. As a theater, the audience sits outside and looks in the only windows. The ticket booth is a patinaed plaque bearing instructions, and a burnished crank that brings the theater whispering to life. Only your coin and your gaze are permitted entry. As you turn the crank, you see a warm flickering image in the eyepiece protruding from the metal walls of the machine. Two footmen in swirly armor hum to life, and draw a heavy velvet curtain, revealing a large clamshell, which steadily lifts its top half in a grand yawn and exposes a venusian figure, who rises in a shy stretch before settling back on the soft bed of the shell, as it closes gently on top of her, and on cue, the footmen close the curtain, before a few blank pages of static flicker to a slow, and the light turns off. A little shrine, an architectural aedicula, and one that is also a simulacrum of the camera and the projector.

the slow-moving image

| Andy Warhol

| Andy Warhol

On July 24 and 25, 1964, Andy Warhol, Jonas Mekas and John Palmer shot six and a half hours of footage of the empire state building as dusk settled over the city and the floodlights atop the tower were switched on and then some time later, off. They shot 11520 feet of film from 8:06 pm to 2:42 am. The raw footage could be unrolled almost ten times the length of the Empire state building itself.

“Empire” the film that was produced from this shoot, slowed the projection of the film from the speed it was shot further, so it became 8:05 long. It is the longest film made by Andy Warhol, although he made other “long films” like “sleep”, a 5-hour film of a man sleeping. Warhol said that cinema was about watching time pass. From the early 1970s, until his death in 1987 his films weren’t accessible to the public, and during this time Empire took on the stature of an oral myth of Warhol’s outrageous persona. It was said to be 10, 12 or even 24 hours long.

It was from this film that I developed an architectural maquette for my thesis project in 2016. The final, larger project on a site on the Lower East Side called for consideration of timber construction, and the maquette brief was to design a viewing pavilion for one of Andy Warhol’s films.

My design responded to Empire as a mirror to the urban landscape. It was a simple cinema, but on the front facade it had another screen: a tile grid that was meant to constantly have its units slowly and continually replaced. a small robotic arm housed in a scaffold-like tower moved on rails across the facade, placing and removing tiles made of an MDF-like pulp, reconstituted from the shavings of previous tiles being shaped by a CNC mill in an annex where the tower would park. The tiles were given depth profiles to look like the various facades of the city, which could be documented by LiDAR scanner. They fit to a grid of spring-actuated clips. Like the serial nature of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen prints and of the images on a filmstrip, the tile grid is meant to be repeatable, and to potentially produce a run of multiples: each unique although occuring in a series or sequence. The circular way that Warhols films are both pictures and dithers of grain, and that his prints are both images and blobs of ink is also reflected in the notion of the tiles being made of a reconstitution of wood: cast from the off-shavings of other castings.

When the sun set the tile grid wall was to be lit from within, with the very thinly carved areas appearing to glow. When each tile was replaced, for a moment the light from inside the billboard sized array would project. Like warhols multiple, they are sort of caught between being like frames of a film and like printing blocks. Inside the theater, the viewing space is like a vacuum tube Television in section, and as a vague viewing space it’s meant to recall lost spaces for cruising and loitering. It’s a place for time to pass 24 hours a day whether or not anyone is watching.

format wars

Some of my fondest memories are from around the days when YouTube was created, when my cousins and I would make home movies together on a DV handicam. It recorded to little magnetic tape cassettes and through itself, it could transcribe them to the computer. We were really impressed by it, and it came while we were still kid enough for it to be used without much shame or hesitation. They existed in our households because our parents had bought them to record us, but in a way only matched by the computer, the camcorder became ours to record ourselves.

We made the silliest home videos with the loosest of storylines; interviews with a puppet, a satire of American Idol… When the office debuted, we assembled at my mom’s office on the weekend and covertly shot a remake of our favorite scenes from the pilot. Then skate videos caught our eye and we started recording ourselves mountain biking and skiing to set to music. We had all that fun on just 640x480 pixels!

That’s a 4:3 aspect ratio and although we definitely didn’t have that terminology then, at the time we could tell you how un-cinematic everything we shot seemed. We could edit in letterboxes across the footage and fake a shakey, handheld 16:9 but it never seemed right, and usually ended up cutting things off in ways we hadn’t planned for. It also made our already fuzzy image even smaller. While any aspect ratio can be adapted to any native format of video, some leave more to be desired than others.

The modern high definition formats all either conform to a wider 16:9 or a 3:2 aspect ratio, but classically many films were shot with a 4:3 aspect ratio. The similarities between classic filmmaking and standard def DV camcorders start and end there, though. No amount of labor or finesse could have elevated the tapes I made with my troupe of cousins to the lovely and still sometimes amateurish image making of a bolex, and yet their footage exists inside the same framelines.

Ironically now the 4:3 aspect ratio has made a resurgence on the artsier side of filmmaking. The popular opinion seems to be that the cinematic look of fifteen years ago, which used 2.35:1 widescreen and anamorphic lens effects, steadycams, etc has become achievable on a budget and thus ubiquitous in a way that it no longer feels cinematic. 4:3 is the classical broadcast aspect ratio for television, and was common in documentary filmmaking, which shared some of the same 16mm production regimes.

Unmodified 16mm cameras record this shape of frame because originally, 16mm stock was perforated on both sides. When the cellulose used in film improved a single sprocket did the trick, and the remaining space where the perforations had been was left to be exposed as a photo-sound track. Super16 is a near-16:9 aspect ratio format that is sometimes done by widening the film gate and re-centering the lens of a 16mm camera. The frame is the same height, but widened into the soundtrack margin. Sound is captured by separate means for these. There are also native Super16 cameras. Ultra16 is a less invasive modification made only to the film gate of 16mm cameras. Because these modifications are made without affecting the lens calibration or position, they can be done much more cheaply than for Super16.

Originally, in the 1920s, the 16mm format was sold as a consumer product advertised as both safer (non flammable) and cheaper than the existing 35mm film stocks. As that space was overtaken by smaller formats over the century, 16mm remained popular for some uses like documentaries and the news for a combination of image quality, stability, camera size and a variety of modern aspect ratios. It places film in a role where it can really shine: small enough to have inherent character in image (grain & unique depth of field), large enough to be vivid and clear, and yet still small enough to be economically shot. A lot of independent, experimental, and student films were shot on it between the 1960s and the 1990s.

video formats compared with the native resolution of 16mm film stock

However, by the time I had a chance to take classes in filmmaking in 2011, 16mm seemed to be on its way to extinction. Excitement had reached a critical mass around the new digital gear that was just over the horizon. Digital SLR cameras had just started to have video capabilities. Around that time I got a Canon 7D as an all purpose camera to document my work and with a limited sense of what was possible to do with digital video from a camera using SLR lenses. I used it a lot during the summer before college in a documentary mode, of my friends and I working at summer camp. I could only preview it because editing software was still almost as costly as a camera itself, but it looked surprisingly vivid and cinematic in Full HD, 1920x1080. With resolution measured in pixels becoming the dominant paradigm, it was only a matter of time before 16mm was surpassed and then qualified as obsolete. Film resolution maxes out at 160px/mm, meaning 16mm film records a roughly 2 megapixel image at 1650x1200 (4:3).

Still, at that time, it wasn’t just my professors nor my own opinion that analog filmmaking was an eccentricity. In 2010 Kodak discontinued a number of film stocks and it was really only available on ebay when I first sought it out. As industry use of 16mm film declined, and more and more documentaries, television series and independent films were shot digitally, the format was largely relegated to student films during the 2010s. In class we were shown a Bolex, and exposed 100’ of black and white film in groups of four or five, but it was almost emphasized as a novelty, as something we were lucky to get to experience as film students, to shoot a 20 second clip as your rites, but not necessarily a practical tool. Strangely, I think in the context of taking film classes at art school, the error of impracticality was no deterrence.

After experiencing a live film set as a P.A. following my first year of college in 2011, I was so preoccupied with the professional equipment I saw that I looked up some of the best 16mm cameras, Aatons and Arriflexes. At the beginning of the 2010s, they could be had for like, a tenth of the going rate the decade prior. Seeing the price of these legendary aircraft-grade feats of engineering sometimes dip below the msrp of the new plastic digital cameras broke something in me.

I didn’t think globally enough to connect the fact that their price was because of the maddening drought of stock to record on. At that time it seemed the format had been phased out, more or less; but to me they were something that lay just out of reach. At the time, the impossible project had just bought a factory in the Netherlands but had not yet produced any film. I remember an early research rabbit hole on producing a lightproof box with rollers, inside which acetate could be perforated and coated in emulsion and wound into a tin for removal. There were a few photos of such a homebrew film-making machine on flickr, but to my dismay nothing like a blueprint could be found. Like I’ve said, the market for the equipment at the time pushed something beyond its limit inside me.

And, on checking back in on the space now almost 15 years later, it seems I wasn’t the only one… There’s an active user community worldwide responsible for a lot of homebrew engineering that all seems pretty reproducable, feasible and well documented. There are well designed tools for developing and scanning that have been fabricated and offered for sale by those in the community, too. After I mentioned to a friend in passing conversation how it had once been an interest, I was curious to see what the market for vintage equipment looks like nowadays, too. And, today: film’s cheap, cameras aren’t.

Today, those same aatons and arris demand around $20,000. And while film is cheaper, it isn’t exactly cheap when factoring the cost of development and scanning and the postal rates at each stage. A 100’ reel of 16mm can record at most nearly 3 minutes of footage. That will cost between $100-$150 after all is said and done, between 75¢ and $1/second. So, again I find myself in a situation that sort of breaks my brain. Film can be had for as little as $30/100’ but processing it makes it something that needs to be either tightly shot or tightly budgeted.

But…

Maybe it wouldn’t have to be if I could develop, dry and scan it myself. I have experience with black and white darkroom chemistry, and I quickly found the kind of development tanks and reels that could hold 100’ lengths of 16mm. The chemicals are simple and cheap, and there are ways to automate the agitation cycles. A drying cabinet with HEPA filters, positive air pressure and laminar flow could be made with very light-duty construction. Following down a rabbit hole, I learned about how a film projector could be run using a stepper motor controlled by a computer that also runs a small camera and LED lights to capture the film frame by frame as a series of small image files.

And there it was. Maybe it could be improved on as I went, maybe expanded to use more expensive and hazardous color chemistry in a cost effective way too, but for the time being, I could see an actually pretty reasonable breakdown of a system for controlling the costs to where I could go wild with the format, in black and white at least. One must become their own filmomat but the with advice and homebrew documentation from the community, this is achievable today. Other anachronistic passions like for instance wooden boat building have cultures that celebrate the absurd, ongoing labors that are entailed in doing it yourself. If the moving image is truly a relative of still photography, I feel confident there’s a pleasure in the every measure of the pain of getting off digital.

I might be alone in that view when it comes to it being a rationale for actually wanting to do things as manually as this, but there is a growing popular opinion that the last 15 years of digital advancement has not necessarily been predicated on the “creative destruction” of all that came before it. Film isn't a horse and digital isn’t a car, it’s maybe more like gas and electric. There are times when a digital format is called for because of various economies, and there are times when film is called for to achieve a filmic sense of moving images that simply cant be achieved any other way. At no point during the rise of digital cinema was 35mm production discontinued. This has always been the way that imaging formats have worked, and film and video today are just contemporary formats.

To stay with the idea of film being the “gas” format, let’s acknowledge a few parts of its nature. 16mm film debuted in 1923, at the same time as leaded gasoline. It was first marketed as safety film, because it replaced an earlier consumer celluloid film that was extremely flammable. Some 16mm cameras contain an oil dispersal system that keeps the internals lubricated. They need to be stripped and re-applied about every ten thousand feet of footage, or every 4 hours of film-time. ‘Footage’ is a real dimension, and the camera usually has an analog odometer to show how much runtime is left on the reel, and a speedometer to show when the motor is moving the film at the correct speed to match the audio recording. There’s an early-aerospace feeling when you hold a machine like this precisely whirring away, completing 24 distinct exposures, pulsing as such through the reflex and the viewfinder and moving about 7 inches of film through the gate, each second, nearly silently. It’s a combustion of light and time contained inside a machine.

Developing is similarly petrochemical, employing bleach, ammonia and borax as well as proprietary chemicals which strip out dye from the film while its being processed. As with automobiles, mechanical speed is a nimble commodity that finds its full substantiation in large unseen reservoirs of chemicals both yet to be used and exhausted. And of course the image itself lives forever on an acetate, although this is the one part of the process that’s archival, and not waste in itself, provided storage conditions don’t cause spontaneous combustion. All of this seems a little gluttonous for the creation of a short run of images, two and a half minutes, give or take. But, then it’s worth mentioning that most modern media is archived by being printed on film stock. Analog trounces digital in this respect, as once it begins decaying it does so steadily and slowly, as opposed to instantly and totally.

‘Invisible’ limitations of this sort, are brushed off as outside of the average use-case, or as an improperly extreme measure of an otherwise dynamic format. Like with a plug-in car, digital filmmaking appears to transcend the consumptive nature of its predecessors. You can lay on the “footage”, which is idiomatic, and capture long sequences in their entirety, limited only by the expansive sizes of storage media, then review everything in-camera instantly. Footage here refutes its origins in a similar way to how mileage does in cars; where originally the odometer measured the distance until the oil lubricating the engine was exhausted. The modern quotation describes how far an electric car can venture on a repeatable series of outings, wherein driving displaces battery charge temporarily. Electric cars don’t have engine oil to change, but they do have limits to the distance that their charges will power them. There’s a tension in a similar way to how footage is applied to both film stock and video files. The terminology meets at a point but diverges.

Digital AV technology itself subscribes to an incrementalism that is different than its filmic forebears, in spite of inhabiting the same name and similarly designed systems, digital and analog cameras are divergent technologies. In the 100 year history of small format filmmaking the improvement of the format involved widening the image exposure area without changing stocks and improving the constituent systems of the camera. Optimization of a set of limited constraints defined the medium. Digital camera technology, having ably replicated and automated the mechanical aspects of photography, and eliminated the problem of film movement, continues to improve the cybernetic capabilities of the sensor: its size, range of color, resolution, and light sensitivity. At each stage of development, new product families were produced in tandem, shaping the next moves for the industry in superficial ways, but never defying Moore’s law. In terms of electric driving, first and foremost you’re encouraged not to question a society and world that depends on and renders all public space and experience unto cars. The “problem” solved by these technologies is just that there was friction in constant and needless consumption. While further privileging driving speaks for itself, digital technology removing the limits of recording may seem benign or utilitarian, but it’s part of the economy that has situated both media and art as “content”.

Where improvements to analog photography and cinematography were axiomatic; like silent camera operation and a recordable soundtrack on film, enabling sound to be synchronized, the improvements made to digital cameras of all kinds are incremental. Last year it could do 10,000 iso, next year it will be 12,500. Except that’s how it was when I last checked in, and today its more like 100,000 to 125,000. The basic reflex to explore the medium through modular tools has taken flight into wild incrementalism, in which the art itself becomes confused with existing within the narrow band of technological capabilities of the very latest equipment. Reporting on the cutting edge of imaging technology, absent any artistic context whatsoever is a predominate form of influence peddling on youtube, with a level of production gloss that gives me a kind of wry-delight because it underscores the mutual confusion of social media creators, audiences and platforms about the distinctions of tool, form and art. These are essentially tautological infomercials in which owning the correct professional tool is positioned as being critical to participating in the artistic discussion, which is itself mostly avoided besides as a foil.

One is reminded of Don DeLillo’s White Noise, when the characters visit “the most photographed barn in the world”. One character opines on how once the visitors have seen the signs showing a photographed view of the barn, they become unable to see the structure actually standing in front of them. As the characters observe the tourists assembling at marked positions to take their own photos of the barn the characters remark on how they are part of a system for reproducing the views of the barn and, looking down a row of them, how each tourist can’t seem to see the others also training their cameras on the barn.

“The artistic discussion” evoked in this youtube content dwells on a sense of tools being “state of the art”, as a kind of arms race to supremacy. In subscribing to this view, which is fixated on the possibility of replicating the quality of the motion picture industry on a ‘prosumer’ video rig, the purpose of a camera and of moving images is so framed. Because the budgetary restraints are removed from shooting digitally, with only the best equipment you may be granted the aura of the professional producer. The aura imparts the sense that wherever you go and use this tool a well conceived product will result, somewhat magically, insofar as it will be a result of the achievable aura of the professional equipment. You will be standing in the right place to “see” the barn, as prescribed on the post cards of the barn for sale.

It’s easy to come across the products of this approach in the prosumer video space of youtube. Besides the “informercial” type, a common variety is the plotless cut of B-roll titled, tagged, and SEO’ed by the equipment used to shoot it with no other commentary. In spite of the absence of anything interesting in the production of the piece, it has a pre-emenince, a sort of cockiness in how it seems to flourish on video platforms. This kind of vague, unfinished content is presented as experimental, but if it was seriously critiqued as such I have to imagine there would be a pivot to situate it as something diagnostic, for internal use among other camera operators. This duality seems related to the prevailing aura I’ve been outlining, where the tool is self evidently the frame for a creative product. The digital camera is a perfectable, consumptive cyborg meant to stand in as a proxy of the author. The camera operator dispassionately adjusts their little pet-artist-machine, but only it sees.

What I see digital video as is a genuine and total improvement over its magnetic tape origins, that can be merged with analog production in interesting ways. But I am less keen to see the latest capabilities of digital recording as distinguishing it as a supreme form. They are just descriptive metadata to me— I take seriously the defensive tack, that the dry content I’ve been describing is just diagnostic material for prosumers. To me, the generative urgency of a limit is a better muse than that of limitless ability. If a worthy idea demanded that I record for many hours at a time, I’d feel glad for the latest video formats.

For most of my ideas, while at first blush the cost of continually buying and processing film might seem exorbitant, it presents a steady rate after the one-time cost of obtaining the recording equipment. The material concerns of accessing a high quality effect are modular and simple. The costs and concerns associated with digital filmmaking at a similar level are fractal-like. All of the parts, each with their own minutiae, will be steadily made obsolete in ways that film will simply remain unchanged. In five years, most of that digital equipment will record a product that is read as a deliberate aesthetic choice. It’s a strange state of affairs that reveals the true nature between the contemporary tech and the legacy formats, still in use by industry, popularly deemed “obsolete”. The aspect of digital tech being able to record infinitely is in tension with the short, insect-like lifespan of its hardware before it becomes obsolete.

The creative destruction of film was an overzealous narrative that after 20 years hindsight can perhaps be forgiven according to the purer optimism of the time about things simply improving without complication, and for taking for granted how capable and adequate the analog formats they already possessed truly were. It’s one of the ways that perspectives have shifted a lot in so short a time, that today so much cultural enthusiasm is focused on the past, however recent. I feel like I have seen the digital format of moving image come into its own from the days that it still relied on tapes as a kind of vestigial, film-like medium. I have lived to see the time when consumers can record at a resolution approaching IMAX film, while at the same time many of the latest innovations are sold on their ability to introduce loss and lower the fidelity of the image. Now long after the thresholds were crossed around 2008, things aren’t so simple as they seemed then.

banner from 127film blog

forum folk

An interesting part of being in my early thirties has been rediscovering long lost senses of myself... I’ve found them preserved on hard drives, SD cards, and online. In ways only I can experience, they feel like equally familiar and uncanny versions of myself. My old profiles attest to a time before either internet or I became what we are today. And while the “enshittification” of web 3.0 churns on and the world at large looks a lot less coherent than it did in 2008, the durability of blogspot and flickr strikes an emotional chord on a few levels for me.

When I first got online, besides instant messaging and early facebook, my cherished memories of the open, pre-SEO internet included a lot of time spent browsing amateur photography on flickr. In highschool, my roommate and I became obsessed with 35mm photography because I took a photo 101 class, became the studio intern, and got us access to the darkroom whenever we wanted. In the first place, there’s a level of satisfaction from metering, shooting and developing your own photos with only mechanical instruments that’s hard to describe, but with pretty unrestricted access to student grade black and white film and development chemistry, it was addictive for us.

our analog camera collection in 2008 — my flickr

A big part of the fun of taking pictures was sharing it with my roommate. All the constituent parts of the art had so much to offer to our conversations, and at each focal point we clarified our interests in it. He was interested in higher performance optics and modern reflex cameras, in which slide film can perform without making any tradeoffs to digital. I was biased toward antique cameras and daydreamt about their linkage to time in all the different ways. I think we both liked how peacock-y they could be as conversation pieces. But nobody else paid as much attention to any camera in the room as we did— our eyes would go to the device and then to eachothers. It was like sports cars were for some of our peers.

But while you can’t test drive or buy a mercedes when you’re a teenager, it was a lot more possible for us to learn about some niche camera or lens, look up a group for it on flickr, see how it “felt” and then after a quick browse through some forums to check prices, click over to ebay and look for a deal. Of course we’d also do the same thing for equipment we could never in a million years afford. We loved to talk about leicas and hasselblads, even if just to parrot what we’d read on the forums.

Social media has never felt as straightforward and purposeful as it did to me in those days. It was not very long after I had gotten an email address, that I used it to start posting on blogspot and flickr. We were years away from the infrastructure to even allow for the notion of an influencer. Although late in the era, hobbyists still ruled the web. Tech blogs like Gizmodo and Engadget were the nascent form of online commerce influencing, along with the creep of new features unveiled at CES each year. The way we used flickr was almost in opposition to the way that the tech blogs seemed to frame what taking photos or recording footage was.

This was the shape of the internet before it was really known what digital spaces like facebook and twitter were even for. Hipster tendencies still hadn’t been coopted in huge ways yet, although I can see now how near at hand that was. I remember having my mind blown as my roommate and I delved into the forums to learn how the more intricate tools in photoshop could produce well resolved effects that made the digital image look cross processed, or like it was shot on slide film. This was probably five years before instagram and its filters for iphone pics, and eight or nine before facebook bought instagram. But in the meantime, we were in those spaces in a way that really feels like a distant memory these days. Except for the curious cases of flickr and blogspot, where, photograph-like, time seems to stay in place.

Enlargers in the first darkroom that I used

I’m indescribably comforted by these living pockets of hobbyism. I remember how navigating blogs used to work— with lists of peer blogs along the margin of the page— and the way that in those days, the internet and it’s vastness emanated from peer networks hosting what was interesting. You could only find your way to something by knowing about it or knowing about something in the network that knew about it. There was a lot more (not simply a different) delight in finding your way around the place, and your route there felt more tangible and recallable, more singular. I have always remarked on how my ability to recall where on a page in a book a memory can be found, and how this does not translate to files on my computer in the same way. Strangely there are beloved websites that are no longer online that feel as local to me as if in a physical book. Maybe because they’re of the time they were in, and not of all-the-time, the way the contemporary internet strives to be, they’re inside me differently.

Although I’ve left my profiles up, I haven’t been a regular user of instagram in about 3 years now. I’ve taken a glance at it a couple times recently and don’t really recognize the goings on in a way that makes jumping back into the social space of it very tempting. Stranger still is the metamorphosis that it underwent during the time that I was an active user, from 2014-20. In the years before facebook bought the app, it was very similar to blogspot and flickr of 2008. I took formalist photos while out and about in my life and recieved anywhere from 0-4 likes from my dozen or so followers, most of whom were current or former classmates; a very simple merger of pre-newsfeed facebook with a photoblog. As my time on the app extended into the trump years and the app became a social media platform in its own right, an era of algorithmic mass-communication and social capital ensued. Without really recognizing the shift, my own use of instagram became involved more in performing my identity to an audience.

It was an interesting place to work out who I am among others but in comparing that time and how it drifted to my early days on analog photo forums and blogs, the internet of today feels tragic to me. It seems clear looking at it in hindsight, that an imagery-based social media space would be beset by the ways late capitalism uses images and socializing. It’s a hard memory to have personally constructed though, along the lines of “this is why we can’t have nice things”. Not hard enough to dull my enthusiasm to keep me from my seeking online— no in fact the opposite.

The survival of places like flickr, and the archival quality of blogspot, while other giants of the day like tumblr have purged ‘inactive’ users, galvanizes my sense that on today’s internet these spaces are more important than before. They are radically pastoral within the paradigm of today’s internet attention industry. I’m not naive to their lack of appeal to tik-tok and short form video-natives. But quite often ephemera of various kinds will trend in the content of the surface web, driving surges of interest to topics that can only be traced into the annals of enthusiast forums, specialty wikis, and the wayback machine. It’s then that the contrast between realms may be at it’s sharpest, and maybe then that a special elect becomes self aware to the same things I’ve been reveling in. It presents to me a sense that it’s possible.

kiki

all zipped up

character/color studies

quick studies, maybe warmup sheets from early 2022

concepts for 'paragon'

visual development for a story from 2020, currently on the backburner…

a fae from 2021

excavating old hard drives!

dollhouse

layers

I spent most of the month working on the interior wall assembly of this tiny house at Hammerstone. An earlier class taught in it had finished with the first layer of rockwool insulation, and the following class on trim carpentry was in two weeks. First came the shiplap ceiling, then the second layer of rockwool set in horizontal furring strips for a thermal break. Next came drywall sheets, primed and painted with a tear-away bead. The final window casings were built in class.

queer carping

I had the pleasure of being the TA for this year’s queer basic carpentry skills class at Hammerstone! It’s held every summer during pride month and its like gay summer camp with saws! I had so much fun helping this sweet group learn by building their own sawhorses.

quilted canvas

Recently, I wanted to make a heavy-duty set of bags for my grocery-getter bicycle. Using duck canvas and bias tape, the seams became thick assemblies. I realized that with more careful planning of the layout of the quilt, the seams could be laid out like a rope basket, within the tote-form of the bag.

good dirt

I’ve been using my compost bin a surprising amount this winter. I’m feeling relieved that the absolute labor of building it over the summer wasn’t for nothing. I also made a video documenting the weeks I spent at that.

It hasn’t gotten up to a stable temperature, but it seems to be turning into a flatter and flatter pile each week. With the cold weather, I’ve been spending a bit less time working on the property, but I started experimenting with some brass sheets to make better roofs for the posts. The roof itself is held together by the standing seams alone. The rivets are made by hammering sections of brass tubing with a ball shaped strike, and are used in the structure that anchors the cap to the top of the post.

offroad research

Internet-World Dispatch

I can usually tell that something has really captured my interest when online search results dry up and I still find myself seeking tenuous leads into the physical world. There’s something tantalizing about information that exists only in print being indexed online. It calls out from just beyond your immediate grasp. A combination of cost, effort and distance stands as a gate separating the merely browsing from the truly seeking.

Sometimes I’ve even wondered if the internet is more shallow than it appears… if it’s mostly conversations between people who are mutually browsing the surface of what is already online, with norms and attitudes reflecting this limited body of references, while the wider scope of that topic may exist in un-digitalized forms or just lie in obscurity online, hosted on platforms that are unknown to the online discourse. That is obviously the case with more specialty information, but I have begun to wonder if it is simply a rule of the current structure of the internet. If by proportion it is most, or entirely a surface separate from and somewhat alienating to real information.

I’ve seen arguments break out on some design subreddits when a basic scholarly approach to theory calls on texts that are outside the niche focus of the community. In a more general way, online subculture has encouraged the idea that everyone, no matter how much of a novice, has a right to subject matter they choose to associate with. Taken together these points have led me to distrust even informal, social sources online, absent any conspiratorial thinking. Now, I mostly think of the internet overall as more of a didactic search engine for the physical world.

As a student, this was most often the case when an online archive was missing a digitalization of a text, and I’d have to track it down to a nearby university’s library. Or more often I’d want a certain tool or material that I had researched online and tracked down a place to buy it nearby. But more recently my use of the internet as a physical-world-search-engine has focused on information that has morphed over its existence from technical data into vintage ephemera. General trade manuals are often digitized but material relating to specific vintage machinery is usually in the wind. By sheer luck and search engine optimization this long obsolete stuff can be found offered for sale alongside vintage postcards and matchbooks on ebay.

Being a lover/fetishist of books and antiques, nothing could delight me more than this overlay. Searching for how-to instructions for elaborate art-making appliances takes one on the necessary detour of browsing online used book stores! Pleasure upon pleasure! I would find myself doing meta-research often; beginning by researching an industrial printing press, then searching for where a surviving one could be bought, then researching the model and what manuals were produced for it, researching the printing process and what trade manuals exist for each of the stages (platemaking, chemistry, press operation, materials, troubleshooting etc.) and finally searching for a dozen or so manuals on ebay. All of this first search just works on a surface level, knowing what to search for but not necessarily knowing more than that about the information contained therein. A successful search just leads you into more of it, but this time possessing a sharper set of terms and a growing sense of intuition about what it is that you’re looking for. There is a sense as you close in on something that you have searched out of a footnote, that you are manifesting the thing that you’re trying to find.

In the end, the thing itself is just a means to more information that couldn’t be found online. These operators manuals contain the program for the machines they relate to, the set of instructions to execute their functions. In terms of my digital/analog rant, they’re the floppiest of disks. Some specify what kinds of electric motors and pumps are used on the chassis of the press and what voltage is needed, which help with the timing of the operation. Others are entirely devoted to exploded diagrams of the machine, isolating each and every internal component and calling them out by name and serial number. These help with maintaining the machine and ordering parts, as well as with disassembly and reassembly. Then there are parts catalogues, which index the diagrammed anatomy of the machine, and list it all in indexes, with coded numbers for each and every one. These have ordering instructions to be sent by mail to a usually extinct distributor, and so serve as a reference point in returning to the internet. Modern reproduction parts are often produced with the same serial numbers or can be found by the tag of the original part number.

At each step from collective social texts originating in the present, online (ebay, hobby and machine forums, youtube, archives), towards individual, ephemeral, mass produced texts originating in bygone industry, (operator/service manuals, trade journals, exploded drawings, parts catalogues etc) Information that is catagorically absent from the other is seen to cause the other’s reality to become more tangible and real out of seemingly nothing. Actively operating the internet this way is in effect a kind of sewing motion, disrupting an sense of technological progress predicated on creative destruction. These hidden hybrids of information, coexisting in time but separated by technological host form, are a truer description of current reality than a linear one that positions analog technology as bygone.

Organon (2012)

Organon was the title of a research project that I worked on while studying abroad at the Glasgow School of Art in 2012. Although I was admitted as a student of print and painting the individually directed format of the studio allowed me to experiment with a research-driven process. I eventually produced a manifesto and two house designs.

The idea of tools as a means to derive order from chaos traces to a greek word; organon. Equal in the definition were the connotations of sensory organ and thought structure. My research began to develop its own internal dogma around low technology, the merging of modern and traditional design languages, and permaculture (zero-waste gardening). There was an admiration of communal shelter from antiquity, and the manifesto engaged more and more with the overall goal of a system pertaining to a unit greater than a single person, and yet was not strongly imagined as a family structure, either.

When I returned to the united states, I applied to transfer to study architecture. The following years imposed their own microcosm of intensity and discipline, and swallowed by the spectacle of New York City, I lost sight of my original vision completely. But the critical framework of my organon research was never truly so buried. Design at one point became a sort of religion for me— representing the essential cosmology of what is humanly possible. I was driven by an interest in the real possibilities of cooperation, and the way that it could be monumentally expressed.

But finding out that the job in so many cases involves trampling some of the existing social fabric and period texture and universally abiding in the whims of the upper class left me bereft. I took some temporary solace in the artistry of drafting, both hand drawn and computer aided, but this was all unsatisfying as the realization dawned on me that I had become caught up in an idea of myself as an architect.

Originally, researching as an artist, I was subject to my own whims and explicitly defied the genealogy of architecture history and the current trade discourse, treating all things as equal in the formulation of a design language built around my niche interests like the amsterdam school and expressionist architecture. I realize now that I was working on an anti-modern project about consumption and obsolescence, but at the time I was proceeding along my own path of logic innocently.

The influence of the arts and crafts movement during my time in Scotland left me obsessed with the concept of a building being the direct footprint of the craftspeople who collectively built it. So my designs for country houses were taken partly from that tradition of William Morris; to have a cell of artisans housed together in self-sustenance, and for the building itself to feed into the loop. I was also bent on fusing divergent notions of architecture as organic and machine-like, by programming silos, wind-stacks and animal pens and bacterial digesters alongside human users as part of the positive feedback loop of shelter being proposed.

Forest Organon

The designs pick up where the texts of utopian catalogues and self-published designs of the 1970’s— authored both by hippies and ‘paper architects' left off, with a repository of “Low technology” that makes an easy link to traditional methods and forms. The designs adapt formal language from the machine aesthetic and the usonian school, contrasting the iconography of le corbusier with frank lloyd wright and bruce goff, to evoke the complex program of the building. Traditionalism in material and construction is decoupled from form, like thatch insulation under the stucco walls of the Narkomfin building). Like a strange mirror to Le Corbusier’s admiration of the grain silo, the organon house is a sort of machine mill for living. But just like mills were very function-driven constructs of their time, the approach for a house-as-mill did not call for stylistic historicism, but rather a kind of vernacular-driven, hand-built functionalism.

Prarie Organon

works on paper

About ten years ago I was making art thinking of myself as a painter. I was trained with oil paints by an intense and dogmatic teacher who was fanatical about one way of putting paint on canvas. Figurative art with direct decisive paint strokes and faceted gradations of observed color were the laws of painting I was taught, along with how to build and stretch a canvas, maintain brushes and handle the paint, thinning media and other arcane chemicals.

In the last few days before I went home for the summer, having finished and packaged my canvases, I dug up some tubes of gouache in a materials closet that I should have been cleaning. When I brought the tiny, rolled up tubes of paint to my teacher and asked to use them he wasn’t thrilled, but I had managed to replicate the pigments of my oil palette completely, which being his formulation couldn’t be argued with. I spent the last few sessions of class getting to know the paints while making two simple observed pieces on paper. I found that if I treated the gouache just as I had learned to use oils, with direct color from the tube & precise mixing on a large mirrored palette, simply using water to thin rather than laquer, they basically worked the same.

They don’t make an exactly comparable image, and there are lots of specific ways of working with either that don’t transfer, but my experience with paint to that point could all be nicely transitioned to a much smaller scale of work on paper. With the dynamics of mixing and opacity being roughly the same, almost everything else was different— shrunken and more delicate. I’m not sure why paintings made with water media tend to be smaller but I imagine that it’s mostly because of how quickly the paint dries, but it could also have to do with the sizes that watercolor paper is cut to. Brushes are scaled to fit smaller work and are much smaller than those for oil and acrylic, have very fine, supple bristles, which feel like they would do well to soak up and hold water. The differences between the two are mostly what have kept me using gouache more than a decade after painting in oils for the last time.

Without knowing exactly how to handle the paints at first, I would make a simple pencil sketch and then painstakingly mix local colors very slowly. In oil I had a rhythm for how my early washes & underpainting would dry and change in workability, but I found gouache dries almost immediately, unless it gets diluted to the point of being more like watercolor. So when I first tried using it, I didn’t try to build the painting up in much of a way, and instead just worked in mostly direct patches, like a paint by numbers.

Even though the size of these two paintings is much smaller than anything I made in oil they seemed to take more time. It felt like I was mixing a color for every tiny stroke. That wasn’t really the case, but it was how it seemed after a few hours of painting 2” square.

That’s why these paintings are left unfinished. There’s a scale factor to the time and physical size of the paintings that almost guarantees this format of skeletal drawing to give some indication of the space and then almost a swatch sample of the perfectly mixed observed colors on a small section of the image. If I had known what I was doing with the gouache I could have probably just as easily mixed enough to lay down color fields and make a proper painting, but this language of empty space and inferred texture is something I appreciated in its own right.

A year or two later, I found this way of working reemerge in montage. Here, where a the unpainted areas are a sort of ground, the collaged elements merge with the paint in an interesting figure with some dimension. This kind of image feels to me like it has one foot in the sketchbook and the other in a wire frame rendering.

This kind of speculative imagery encompasses both sketchbook fantasy and virtual reality. It still uses a sample set of colors to render out forms with surprising clarity. The image is nearly complete and almost insists on having some negative space as if to deny the stature of the kind of advertising illustration that it mimics.

Another year or so later, in 2013, I made a pair of mosaic paintings that worked like a multi-directional space-comic. Depending on which direction you read, the space of the painting can be explored on a few paths. Because of when I stopped working on the paintings, the further extents are represented more and more sparsely. There’s a quality of how a memory might look mapped out from the point of most vivid recall, out into more and more tangential and sparse elements.

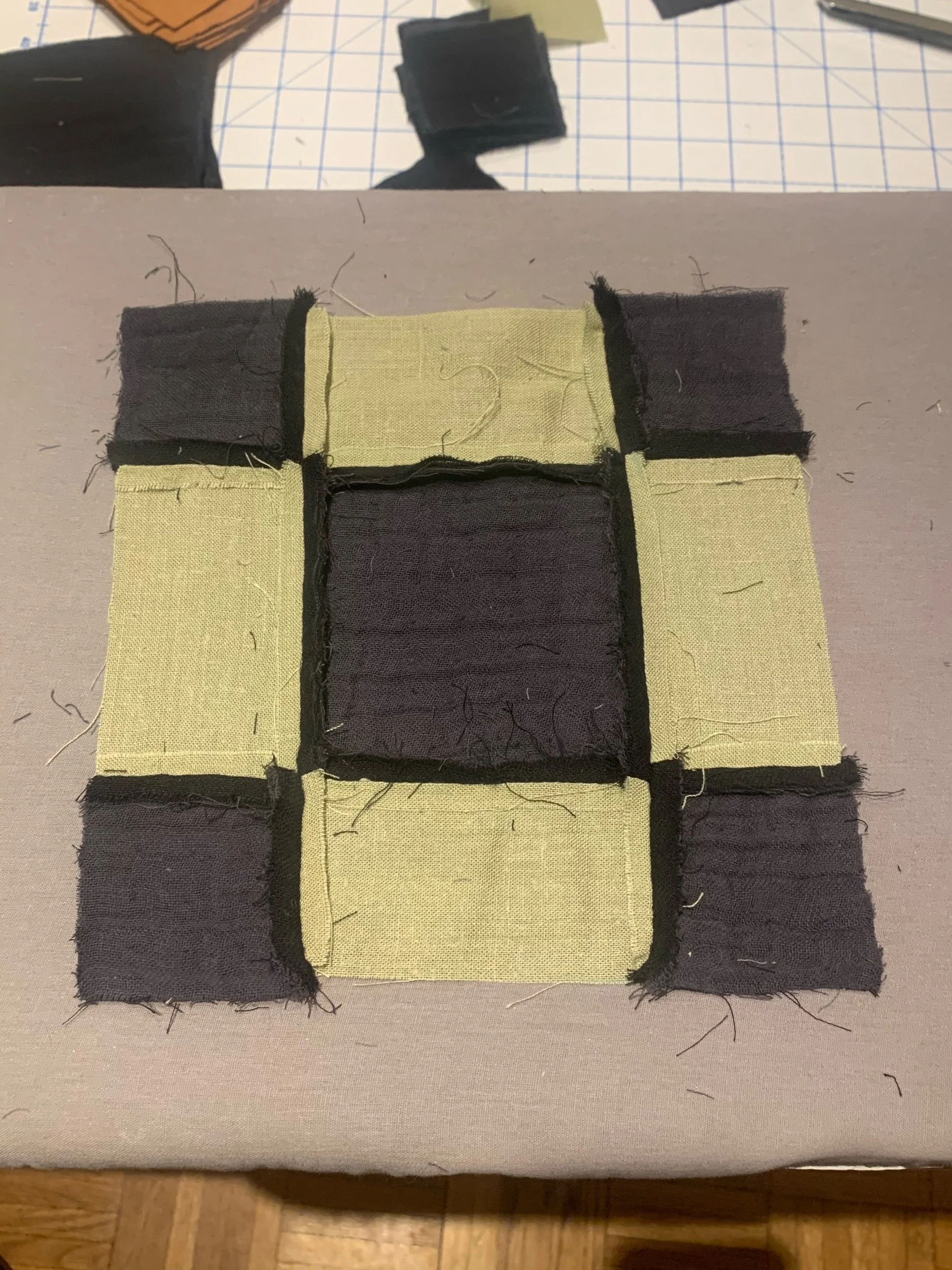

amish 9-patch

Over the winter I spent my idle hours learning the basics of quilting. I made a design for an Amish 9-patch, which can be as simple as a 3x3 grid of squares, but I played with the proportions a bit. When stitched, the small corner and side pieces join to make an inferred grid the same size as the center square. Despite the simple repetitive actions involved in quilting, it takes a lot of time to complete rows! It really is an antiquarian way of passing the time. I only got about half way done with one side of the quilt by the time the thaw came. Next year!